As in any other human discipline, to a certain extent, scientific analysis can be applied in gastronomy; and the combination of flavours in culinary dishes, with the aim of knowing and enhancing the richest or most intense, can be unravelled with a chemical examination. This is what Kikunae Ikeda, a professor at the Imperial University of Tokyo, did in 1908 with the broth of the seaweed kombu. He discovered in this way that the salt of the amino acid monosodium glutamate (or glutamic acid) had a different taste, which he called umami.

What is ‘umami’ or the fifth taste?

Umami is considered one of the fundamental and recognizable flavors along with sweet, bitter, salty, and sour. That its existence is widely ignored in the West, in the matter of everyday eating and the importance of enjoying banquets, is perhaps a question worthy of a thorough cultural study. As a Japanese term, it was coined by Ikeda himself, uniting the pre-existing umai and mi, which mean “delicious” and “flavor” separately, and which could be translated into Spanish, and we apologize for the redundancy, as “tasty.”

Specific taste receptors in taste buds anywhere on the tongue can detect it. According to Shizuko Yamaguchi, a researcher at Tokyo University of Agriculture, umami is a difficult flavour to describe because of its paradoxical subtlety, as its presence lingers on the palate and produces a velvety sensation in the palate that is also felt in the back of the mouth and throat. And Edmund Rolls, a neuroscientist at the University of Warwick, has noticed that it enhances other flavours.

Origin and history of ‘umami’

As we have said, Kikunae Ikeda discovered umami and gave it a name in the first decade of the 20th century by relating it to monosodium glutamate. But it had already been used thousands of years before in the kitchens of very remote places in the world without knowing that it was there. The Chinese philosopher Confucius (552-479 BC) wrote that a condiment containing it, the result of the fermentation of meat with cereals, alcohol, and salt water, was essential for preparing very appetizing dishes, for example. And, in Ancient Rome (200 BC), it was found in garo sauce.

Much later, the French chef Georges Auguste Escoffier, whom William II referred to as “the emperor of chefs”, offering a wide variety of gastronomic proposals in his exclusive restaurants from 1878 onwards, combining umami with the other four basic flavours. Then, in 1913, it was Shintaro Kodama, a disciple of Ikeda, who revealed that the IMP ribonucleotide from dried bonito flakes has the same characteristics as glutamate. And Akira Kuninaka added the GMP ribonucleotide from shiitake mushrooms in 1957.

Examples of foods that have an ‘umami’ flavor

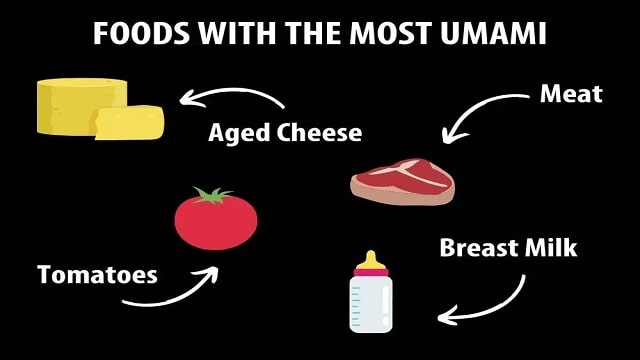

Apart from those already mentioned, from kombu seaweed, fermented meat, and garo fish sauce to dried bonito and shiitake mushrooms, there are many foods that bring the aftertaste of umami to our palate. The fermentation of meat we were referring to, in fact, is seen as the origin of bean paste and the very popular soy sauce. But we also often stumble upon it, without knowing it, in:

- Ripe and dehydrated tomatoes

- Anchovies

- Sardines

- Cheese

- Cured ham

- Chinese cabbage

- Spinach

- Green Tea

- Seafood

- Many edible mushrooms and fungi

Although MSG is found naturally in potatoes, it can also be added to other foods to enhance flavour in Escoffier-style restaurants or as an additive in supermarket foods. Potatoes and olives can be irresistible for this reason, as, according to a 2005 study by the Complutense University of Madrid, they increase the desire to eat them by 40%.

What’s wrong with monosodium glutamate

However, it couldn’t all be so pretty for the most incorrigible gourmets. Not to mention that something as defensible as breast milk entices babies with the umami taste. Its artificial stimulation of neurons can harm our nervous system because it exhausts them and some can even die. In addition, monosodium glutamate can cause us from simple headaches, migraines, sweating, muscle spasms, and nausea to allergies, cardiac irregularities, epileptic attacks, and depression.

Excessive consumption of umami has been linked in studies to a greater risk of developing multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s. And, since it prevents us from feeling full when eating and spurs on the craving for products that use it as an additive, it can lead us to ignore the risk of obesity, which in itself causes serious illnesses and greatly worsens other pre-existing pathological conditions. So, be careful with umami, fellow diners.